Welcome to the Chapple Big Fish Lab

In the Chapple Big Fish Lab, we study sharks and other large marine predators around the world focusing on their movements, behaviors and population dynamics. From South Africa to Australia to California, using state-of-the-art technology and techniques, we sample and electronically tag animals to gain insights into their lives when we aren’t there to observe them. In Oregon, we leverage partnerships with industry, management, science and local communities to study the sharks off our coasts to better understand the roles these animals play in our marine ecosystems and economies. Relatively little is known about how sharks affect our coastal ecosystems and communities in the Pacific Northwest, but here in the Chapple Big Fish Lab, we are changing that.

Did you know?

The Pacific Northwest is home to at least 15 species of sharks?! They range in size from the Brown Catshark (~2.2 ft or 65cm) to the Basking shark (>30 ft or 10m), with lots of sharks in between. To learn more about the sharks of the PNW visit our Sharks of Oregon page and explore the different species off our coast.

Shark Sighting in Oregon or Washington?

Tell us all about it on our Shark Sighting page to help us better understand when and where sharks are along the PNW coasts.

Chapple Big Fish Lab DEI Statement

In the Chapple Big Fish Lab we acknowledge there are systemic barriers and inequality in STEM fields- especially in shark science- and are committed to increasing representation of historically underrepresented groups in science. We are committed to inclusivity and strive to make access to research, opportunity and experience more equitable. We value diverse thought, experience, preferences and skills and feel we are stronger and more powerful as an inclusive community. We also acknowledge that we still do not fully understand the impact of historic and systematic inequality and as a lab we continue to actively evolve and work to fully represent the diversity of the broader global community.

As a largely field-based lab, we appreciate that field work can be intimidating and unwelcoming and we strive to create safe and accessible work space for all. We also participate in the FieldSafe program at OSU, to ensure that field work is safe to people of all identities.

Our Specific Actions

- We acknowledge the diverse cultural context of our work and integrate various types of knowledge and value in our interpretations and presentations

- We strive to offer opportunities to recruit and mentor students from diverse backgrounds and experiences.

- We use science communication to make science and research more accessible to people of all abilities Learn more about our ORSEA and OCEANTRACKS curriculum.

Who are we?

You can also see our team of scientists and students on our People page.

What do we do?

Want to know more about the research that we do in the BFL? If so, check out our Research page or follow us on Social Media.

In the News

"It [Jaws] villainized sharks and people became absolutely terrified of any species that was in the ocean," James Sulikowski, director of the Coastal Oregon Marine Experiment Station at Oregon State University, told ABC News.

Natalie Donato is an Honors junior in the College of Science, majoring in Marine Biology and Ecology with a minor in Biological Data Sciences. Natalie’s specialty in Marine Biology, her work in Chapple Big Fish Lab, and her...

Vouchers are now on sale for a new specialty Oregon license plate that researchers hope will inspire people to think differently about the sharks living just off the Oregon Coast.

Using a monitoring gadget akin to a FitBit, paired with a camera, researchers gathered data that gave them a rare chance to understand how collisions with vessels affect massive sea creatures. These accidents are becoming a bigger issue...

“It’s more often than not a shark is going to see you than you are going to see the shark. I’m sure this fisherman has had a shark around them before,” said Oregon State University professor Taylor Chapple.

Did you know...

The Dwarf Lantern shark (Etmopterus perryi) is currently the smallest known living shark species.

(Springer & Burgess, 1985)

Broadnose sevengills are listed as “vulnerable” globally by the IUCN Red List, with the most recent assessment of the species completed in 2015.

("Jaureguizar AJ, Cortés F, Braccini JM, Wiff R, Milessi AC (2021) Growth estimates of young- of-the-year broadnose sevengill shark, Notorynchus cepedianus, a top predator with poorly calcified vertebrae. Journal of Fish Biology")

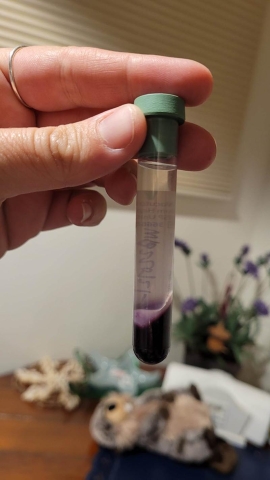

Some of us in the BFL are looking into shark foraging ecology (aka what they eat). While collecting stomach contents tells us what they're eating *right now*, blood and muscle samples can tell us what sharks have been eating up to 12 months ago!

Some of our partners

- University of California, Santa Cruz

- NOAA, NWFSC

- NOAA, SWFSC

- Virginia Tech

- Ireland Basking Shark Groups

- Arizona State University